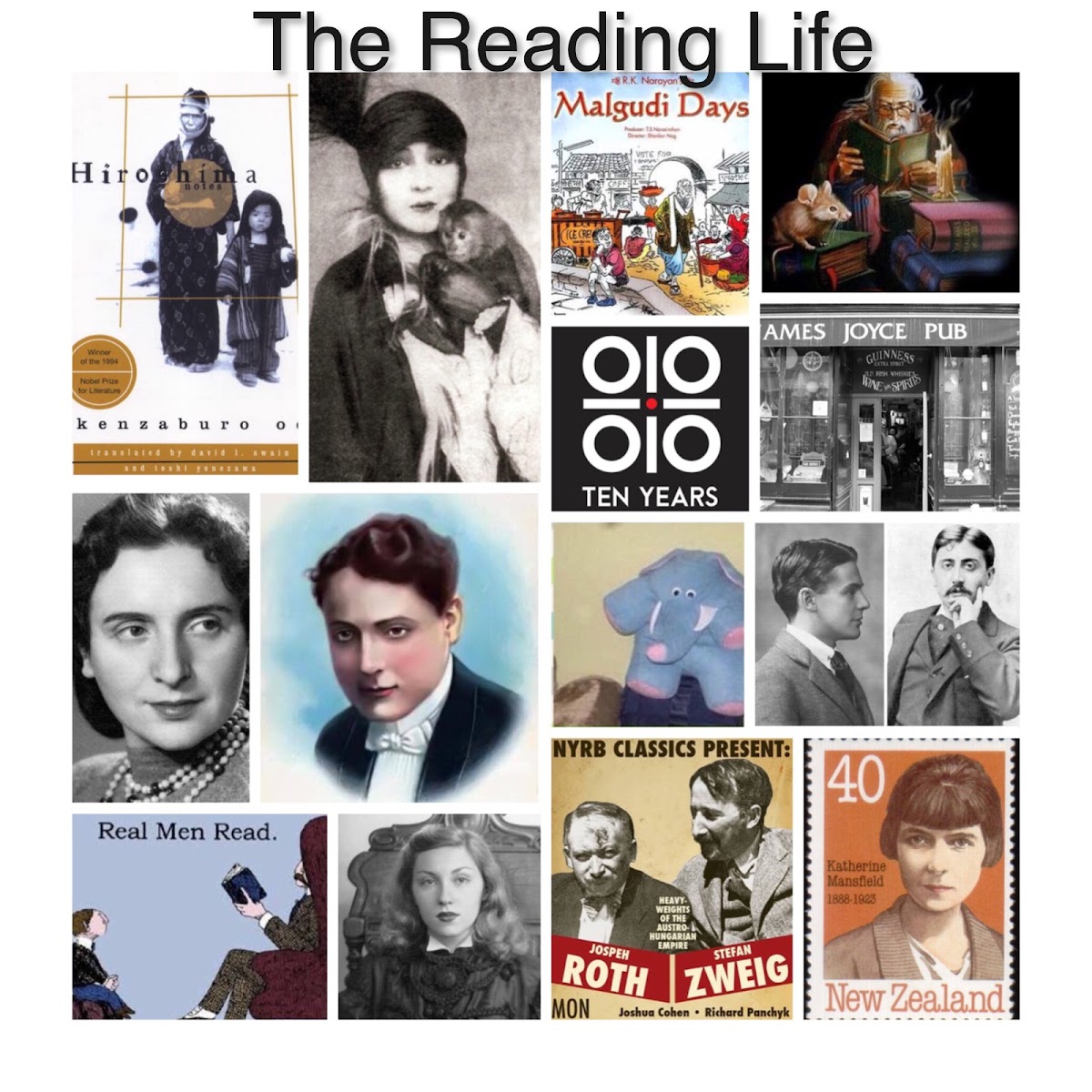

In November 2011 I read and posted on a superb collection of short stories,

Ivan and Misha by Michael Alenyikov (2010, 210 pages).

One of the biggest side benefits of editing the Reading Life for 4.5 years is the wonderfully creative artists I have become acquainted with. Among them is Michael Alenyikov. We have never met and probably never will but the wonders of social media and e mail has allowed us to exchange thoughts regularly. I am proud to be able to present to my readers a wonderful short story by Michael.

Below is an extract from my post on his marvelous collection of interrelated short stories, Ivan and Misha.

Ivan and Misha by Michael Alenyikov is an interrelated set of short stories about two fraternal twins, one bi-sexual and one gay, and their father, Lyov. The first story is set in Kiev (the largest city in the Ukraine) in Russia, where they were born. In the brief prologue (set in the 1980s at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union) we learn that the wife of Lyov and mother of the boys died before they were six. The father is a doctor. We learn he only received one year of medical training and was sent out into the horrors of WWII in the Ukraine to remove limbs from soldiers, without anesthetics. They live in a large apartment complex in the style of the times. The father keeps promising his sons a better life, a new mother, a new apartment, but nothing really happens until he moves the family to New York City and the stories start in the late 1990s. Alenyikov gives us a wonderful feel for the immigrant experience. The characters are brilliantly realized. I give my highest endorsement to any lovers of exquisite prose and the short story.

Ivan and Misha by Michael Alenyikov is an interrelated set of short stories about two fraternal twins, one bi-sexual and one gay, and their father, Lyov. The first story is set in Kiev (the largest city in the Ukraine) in Russia, where they were born. In the brief prologue (set in the 1980s at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union) we learn that the wife of Lyov and mother of the boys died before they were six. The father is a doctor. We learn he only received one year of medical training and was sent out into the horrors of WWII in the Ukraine to remove limbs from soldiers, without anesthetics. They live in a large apartment complex in the style of the times. The father keeps promising his sons a better life, a new mother, a new apartment, but nothing really happens until he moves the family to New York City and the stories start in the late 1990s. Alenyikov gives us a wonderful feel for the immigrant experience. The characters are brilliantly realized. I give my highest endorsement to any lovers of exquisite prose and the short story. "There Is no Future In History"

By

Michael Alenyikov

Buffalo’s outskirts came with an icy edge to the air. Samuel fumbled for the handle to raise the Subaru’s window. Damnation, he thought, forgetting, remembering there was a button to press not a handle to turn. The sky's gray darkened and lowered. Flecks of white fell-- ash or snow? One was never sure passing the steel mills that guarded the southwestern approach to the city. Memories here. Someone had died. Murder? No, assassination. McKinley or Harrison? Surely an easy one to hit out of the park for the likes of Sam, Professor Emeritus of History, on the road to settle his brother’s affairs, to bury his body in Boston, from which Charlestown Sammy had fled a half century ago.

Too damn easy a question to fumble.

In search, he traveled down the mineshaft of memory and caught sight of . . . Who? . . .Himself? No, the hair was too dark. And where's he leading me, kicking about the neuronal pathways, trapped in a maze of past and present and the what do you call the only-moments-ago? The figure stopped, turned; a coy smile appeared, more of a smirk, but just as quick the stranger brought a handkerchief to his face, coughed, covering all but his eyes. It's mine! Samuel thought, the smile was mine; but as if in reply, the well bred-voice he could not quite place said: “Oh, Sam, how easily you forget. I taught you how to woo them with a glance and a grin, and it didyou well with the boys back when. And wasn't it I who said to drop those specs, so badly patched, for the owlish ones the visiting boys from Oxford wore?”

Overhead a sign and arrows demanded: Niagara Falls, Downtown, or Thruway East. Samuel studied it through lenses, thrice-lined, which still confused him to no end. Settled on the eastern path, then Wham! The well-bred voice, kicking at a weak spot in the mine shaft, demanded: “What’s the difference between a murder and an assassination?” There's an interesting article here, Samuel thought, although a minor one. “Quick, Samuel, an answer, an answer,” insisted the well-bred voice . . . “My name will be the reward. In time, of course,” the homunculus teased.

“And you've lots of that.”

Sarcastic bastard.

Fame has something to do with it. A fatal blow to my head by a frightened mugger would be a murder, the killing of a President, an assassination. Samuel’s stomach growled and gurgled -- hunger or gas? They were becoming harder to tell apart until a spot of nausea announced itself; my mind is stiff, he thought, my stomach loose; there’s no point in resisting change, he'd learned over fifty years and those many yoga classes during his San Francisco life. But he’d never stopped taking notes and the objectivity that he’d practiced all his life -- as rigorous as any meditating monk could claim – gradually calmed his agitation.

Who did die in Buffalo? The spreading nausea needled his vanity; what am I without my facts, names, and dates to anchor the past? He was in truth a catalogue of pain: head, stomach, back, knuckles. But pain, at least, was a presence, demanding attention, providing direction, if only the selection of doctors. But loss, losing, was sadder, the shock of absence.

Yes! He’d had a fling with a boy from Buffalo -- a memory sprung loose, a tender spot, an artery not yet hardened. (There was more than death in Buffalo!) He was a fellow student inhistory at Harvard, that castle overlooking the wrong side of the tracks where home lay hidden, modest in its shame. He’d crossed the moat, scaled the walls, but not his brother, Petey, and the talk between them had turned small: sports and weather; the melancholy Red Sox, the triumphant Celtics; Ted Williams, Bob Cousy; the hated Yankees -- the theft of Ruth still raw years later --The weather in New England and oh how if you wait an hour it will change . . . the conversational fallback when there was nothing more to be said to the person who’d become a stranger.

“Them Sox,” he’d say, tossing a ball into the space between two beds.

“Yeah, them Sox,” from Petey, the ball sent back as it had a thousand times and more.

“They always fold in August,” says Samuel. “I told you that,” said now with Ivy League authority.

"That Williams, better than before the war."

"He's not the same."

"No way," from Petey.

"Best years he gave up."

Petey, standing, and then limping towards the kitchen, "There'll be better ones."

"You bet," Samuel'd say, not pushing his advantage.

Samuel’s fingers searched for a knob to twirl away the ear-jamming rap rap rap of the angry man on the radio. But it was buttons again to push, too small for his no longer nimble fingers to find as he fiddled through sounds: past country twang; you get what you need from the Stones; and a praised-be-god lucky landing on an island of Mozart, the tinkle of piano keys, though tinkle was hardly the word for Mozart.

Nimble fingers the boy from Buffalo said Samuel possessed. Samuel of the nimble fingers. He called him my Adonis once while making love, just once, but the words rang in his mind with the clarity of a bell as Samuel pressed foot to brake to slow the car for traffic; and those words carried more historical weight than anything Samuel'd studied since, towering over the details of Reconstruction, the overlooked strengths of the Grant administration, the catalogue of foolishness following Lincoln’s death: now that was an assassination to reduce whoever died in Buffalo -- Ah! McKinley it was! -- to a mere sordid murder. My Adonis, the boy moaned, body shuddering in his Buffalo home, boyhood bedroom, muffling sounds so as not to alert the parents. They’d shuffled off to Buffalo to see the family for Christmas. But what was the boy’s name? The soft skin could be recalled, the coarse hair on his legs, the stubborn red spots of acne on his chin. “Fuck me,” he’d whispered (no one had ever dared to say that word; what a shock to learn sex need not be as silent as Communion), which Samuel tried but fumbled, and -- what did they call it then? Yes, friction had to do, and did quite well.

“Shuffle off to Buffalo,” the boy had said once too often on the train ride from Boston, passing the bare limbs of trees in the Berkshire hills -- dabs of painterly white clinging to the evergreens -- and after, as they fitfully slept, Samuel's head resting on the other boy's shoulder while snow fell on farms between Albany, Utica, Syracuse, Rochester and Buffalo, cities strung along the tracks like a necklace of costume jewelry. Yes, too often said, enough to poke a hole in Samuel’s infatuation, allowing what had been love to seep out. “Your modus operandi,” a friend had named it many years later; “Proof your real self can love women,” a psychiatrist counseled after that embarrassment with the security guard in the men’s room. (He'd been bailed out of jail by an older friend who tutored him in the ways when he was fresh to San Francisco). "Who hasn't been cuffed in the toilets," Albert had insouciantly added later. An eye for detail was anasset to a scholar, but as a lover it proved his undoing. How many were there? How many conquests?

“You’re the historian,” the well-bred voice scolded, coughing into his handkerchief. “Peter was the accountant. Seeing the meaning is your vocation,” he said -- taking on a kindness that Samuel did not trust -- “Not the body count.”

The boy from Buffalo took a master’s degree and decided there was no future in history. “Come with me to Buffalo?” in his eyes their last night, walking brazenly, hand-in-hand along the Charles, safety in a moonless night on the Esplanade, the sound of unseen others padding along the damp grass, grazing the bushes with elbows and knees, an occasional bat caught in the lamplight, and on the wind the fishy smell from the harbor.

From the Subaru’s radio a piano struck a chord, different from those preceding, Mozart subtle as ever prodding him to move along, changing the mood. Something else had changed that year. The homunculus grew edgy, angry, bouncing himself off the hard tunneling walls of the mineshaft. Trying to hurt himself? Or Samuel? Samuel’s grip on the wheel wavered and a horn’s toot-toot returned him to his senses. He slowed to think, impeding the flow, creating a blockage, a traffic jam: an interesting phrase, whose roots he pondered until the horns transformed into one harsh wail that he thought was likely the same that Dante heard as he explored the nether regions of hell. He took a deep breath: cold winter air, the tingly smell of snow. Yes, it was the English Professor’s suicide that year. (The year? The year? Had the Korean War started? Yes? No?) It had cast a pall on love. Why bother, we all thought, rebuking desire. Why bother when he is our fate. And the Professor's name? Samuel struggled to recall, inching the car along to the cries surrounding him, abandoning the struggle with memory, which brought relief and a sigh: I've acoffin to select, after all! Now sucking in air so hungrily his lungs filled past where the cigarette habit had once erected a barrier.

How sensual memory is when one struggles for it. Is this perhaps what’s to be looked forward to? But the boy’s name, his look, the color of his hair, all these eluded him, and the urgency to remember was upon him again. The friend who’d tagged his modus operandi in love had added stubbornness, too; or was that what the boy cried when Samuel (a boy, himself) said he could not join him in Buffalo? “I’ll stay here, with you, then,” the boy had said, but yes that was the year of the Professor’s suicide and Samuel was rapidly learning -- as were they all, except perhaps for the lovesick boy -- to watch his back.

The white flakes were definitely snow. Samuel reached for the thingamajig, turned and swish, swish went the wiper blades. He felt relief beyond compare; the damn thingamajig was where it had been for year upon year. He stared intently ahead as snow covered the windshield and was nimbly brushed away. He had had nimble hands. He’d been told that by the boy fromBuffalo -- Yes! Frederick was his name, his hair was dark and tightly curled, and this memory released the muscles of his jaw and his hands clenched the wheel tightly in the effort to steer the Subaru through the sleet; but the rest of him now softened and he could feel again Freddie’s hands, and how he’d admired Sammy’s own firm touch. Modestly (not false!), he'd said, it came from throwing baseballs all through high school and his three years at Harvard. It had been fall, and leaves, red, rust, orange, a jaundiced yellow, swirled outside his room, the window rattling in the wind. Samuel dug through his closet, retrieving a scuffed and tattered baseball. “You’re joshing,” Freddie said, incredulous on his face until Samuel showed where fingers were placed to achieve a sweeping curve, give the ball speed, or slow its pace; and he remembered nowFreddie's own deft fingers probing him in turn, until he found where Charlestown Sammy had let no one touch before.

The memory of that touch pleased him for tens of miles, perhaps a dozen highway exits, until the nausea demanded attention so swiftly that he pulled to the side of the road. Heedless of cars rushing past, he opened the door, and leaning on the car for support, stumbled to the safety of the passenger side, where he vomited whatever ate at him. He retched until there was nothing but bile, as the rapidly falling snow covered the greasy bile and the brown, red, and green (touched with yellow) colors of the bacon, eggs and jelly donuts that had offended his body.

He stood and turned. Across the highway the gray-blue waters of a minor lake (plans to see the Great ones forgotten in this race of his to cross the continent) lay flat like a mirror. Was a suicide a murder or an assassination? The thought returned and did not let go. He saw the English Professor's body lying still on his sitting-room floor. It was a memory of an event he hadn’t seen, yet it was more real to him now than the dry heaves, the hard ache in his belly, more real than the cars hurtling by, dangerously close. The news had spread across campus and the image was born, in that year, 1951. It had horrified him. So real the body was, skin pale, blueish with death. The gray, bluish corpse now rose in Samuel's mind and beckoned. “So standoffish are we? Nothing to be afraid of. Really. As to your question,” he continued, with that note of ironic detachment, the code by which Samuel had learned to spot others of his kind, “It depends on the fame of the victim. Surely that’s obvious, Samuel.” The English Professor had been anything but ghoulish that time Samuel'd taken cocktails with the others in his home on Beacon Hill. Then he was short, round and bald, a shy manner of speech, his face puffy with middle age, cheeks stained red by rosacea he'd tried to cover with talcum, but very much alive in the reflected light of the young men who surrounded, adored him, protected him from the most recent urgentwhisperings that he was a communist, a sympathizer. In memory, Samuel conjured the unnamed sorrow in his eyes, but not then; then his eyes had raced to capture the Emersons, the Melvilles, the Hawthorns, Jameses, Poes and Whartons (“original editions” a reverent sophomore informed Samuel) that lined his bookshelves; the Renoirs and Manets (“Copies, of course,” said the same sophomore, “But, superb, don’t you think?”); and the oriental vases and silk screens that adorned the flat.

“I’d like to think my death was an assassination of sorts, but you’re the historian, after all, dear Samuel,” spoke the animated corpse, as soft-spoken (to hear him, one had had to lean in back then so close as to feel his breath) as he’d been in life.

A police car slowed, pulled over behind the Subaru, red lights swirling. The policeman, deliberate in pace, bowlegged in walk, approached Samuel. “You okay, old fella?” he said, a wide-faced, barrel-chested cop, with a nose that looked to have been broken more than once.

“Yes, yes,” Samuel said. “Just needed some fresh air.”

“Well, best to take your fresh-air off the highway. We’ve some nice parks back in Buffalo, you know.” Samuel waved him off. His mouth tasted vile. He scooped a clump of fresh snow with an ungloved hand to wipe his face, but could not contain a smile. Assassination, indeed. Wit from beyond the grave.

Samuel tugged gloves onto fingers red and stiff with cold. He had been on the road for five days. The muscles in his leg and groin ached. In such a hurry to pick out a coffin, he had to laugh.

Samuel lost his way in a cluster of signs leaving Buffalo, the nausea a dry ache. He seemed to be -- no, he most certainly was -- driving in circles. Surely, he’d seen the exit to Tonawanda -- or was it Lackawanna? Cheektowaga? -- a half hour earlier?

Swish, swish, the wiper blades, the wet snow heavy now. To the right, a sign proclaiming Rochester ahead and Samuel swerved quickly, imprudently, feeling the car wheels slip, lose traction: which way to turn the steering wheel? There was an answer to this question, but it was not a professor’s rhetorical; it was his father’s voice saying, “Which way, Sammy? Think, for chrissakes,” Da shouting as the Rambler had slid along an unexpectedly icy Cambridge street, Samuel’s heart pounding, his mind failing him. ("That head on your shoulders is your best asset," lisped bow-tied Mr. O’Connell, who'd advised him at Boston Latin. "Forget the baseball, I would, if I were you," he'd said, and Samuel flushed even now with anger -- an old Auntie, he'd joined the boys in calling him.) And Da going on, “Steer, you idiot, steer.” But which way? Into the spin or against it? And Petey in the back, taught by their father to drive the year before, laughing, “We’re going to die. Sammy’s going to get us killed.” Choking on his laughter, doubled-up -- Samuel knew without needing to see, relishing the tables turned. Petey would easily have died a happy death, to see his college-bound brother look the fool in Da’s eyes.

“Turn against the spin, Sam, against,” a tremble in Da's voice, a squeak, an embarrassing high note, a startling departure from his baritone, which made Samuel ashamed for his father even as he struggled with the wheel, managing to guide the spinning car to a stop, hitting no cars, no people, despite a full 360 in Porter Square. 'You old Auntie' lay unspoken, then relief in Da's manly "I'll take over now, Sammy."

Turn against the spin! which he did, feeling as pure a joy as he could ever recall in the return of reflex. But a sharp stab in his upper back like a sliver of ice between his shoulder blades dumped Samuel fully into the present. He cut into the right lane and slowed to under forty. Too high in the back for stones brought relief, calmed his mind, before other options death offered could be explored.

Swish, swish, the scrapped the wiper blades. The English Professor, they’d called him a swish, the worst said it with disdain, but even the adoring ones . . .

Hard to watch oneself for a lifetime.

Samuel took the cigarette he'd placed snugly behind his ear in Ohio -- medicine for rawnerves -- putting it between cracked lips. He continued to crawl along in the old man's lane, glancing down, courting death, to find the dashboard lighter. There'd been laughs long ago when Samuel'd aped James Dean's way of tucking a cigarette behind his ear. (Had he really once said, "I'd die for a night with him in my arms"? Had he really lost days, no, months of his young life, prowling San Francisco’s bars and streets for anyone with the movie star's looks, his slouch, his come-hither eyes?) Though he'd thought himself an anguished soul, he remembered it now as a magical time, and the memory carried him to Rochester, collapsing the time into one long moment of unexpected sweetness.

Passing Rochester he wondered: Any assassinations here? Was there any history to this town? None he knew, beyond a layering of Eastman and Kodak. He’d be passing near the Erie Canal soon, somewhere east (or was it west?) of Syracuse. History in that, but not his: he'd defined his interests to what came after Lincoln: the follies of Reconstruction; the what-might-have-beens; Grant’s potential for greatness squandered by his trusting nature. Too late, colleagues had said, you defined yourself too narrowly. You’d have gone further with a wider vision, a broader reach.

Rochester behind him, the drive to Syracuse passed slowly, time enough to brood about the shoulder pain, and then, damn it to hell, his demanding bladder. He pulled over at a rest stop outside of Syracuse for gas, and to pee. Business done he walked around the empty picnicbenches to stir the blood, but felt disturbingly weak, unsteady at the whims of a brisk wind. He feared a stroke and searched his limbs for the telltale paralysis and numbness he'd learned of on TV. None found, it registered that the sliver of ice in his back was gone. A fair exchange? One dread for another. Inside he bought coffee and a candy bar. “Yes, please, thank you, have a nice day" exchanged between him and the girl behind the counter who wore too much lipstick, a purple close to black, but had pretty blue eyes; and his own green eyes discerned the glitter of an engagement ring: still in high school he presumed, too young, he judged, pregnant? he questioned.

Behind the wheel again. Caffeine, sugar and a return to lucidity. Relief in a problem solved. Blood sugar, not the buildup of plaque in the arteries, imagining it to be much the same as tooth plaque but in the brain, wondering why a simple brush and floss were not the cure.

Platitudes. Thank you. Have a nice day. The weather in New England. His mother’s hands through his hair, distracted, reassuring . . . nothing to say, saying so much: “I’m here. I’m here.”

When had he and Peter slipped into the smallest of talk? It brought to mind that movie he’d seen when he first moved west -- what was the name? Yes! The Incredible Shrinking Manor was it Woman? He wrestled the question until a horn woke him to his wavering again across the highway’s broken line. When did small talk shrink to nothing, to a bond so small as to be lost?

The urge to pin a date to the moment was as strong as his bladder’s urging before the rest stop. Silliness, he judged. Like pinning down the moment Lincoln found his full courage to renounce slavery; silly even to make such a comparison between his life and the life of a nation. Such airs you put on, old man. Peter was no more, a corpse awaiting a coffin; their parents were no more, a family gone to dust.

The candy bar and soda were a mistake. Samuel felt the falling of blood sugar, a familiar cause of wasteful melancholia, which set him adrift into the years after James Dean's death when he'd prowled streets and bars in search of his own Tab Hunter. How much more real they were, those movie stars, than the flesh and blood men who shared a bed with him for a night, discarding each other in the morning as lacking that certain je ne sais quois.

Swish, swish. The wiper blades squealed their way across the windshield. Samuel of the nimble fingers brought them a halt. The snow had stopped. He glanced away from the road at the mile-after-mile sameness of the terrain, so unchanged from the past. Farmland brown, crops harvested, the land a naked supplicant awaiting winter, monotony broken only by patches of fresh snow, and a scattering of houses, barns, and black, white-spotted cows indifferent to the fences surrounding them. It wasn’t that Petey hadn’t seen how Charlestown and its ways hadcontained them both when young . . . and that Samuel was the one with gifts a world values. Butmight it have been that Petey lacked the drive to leave? Or might it have also been that Petey had a deeper affection for home, a depth of love missing in Samuel? A kind of love, a passion -- that search as he did Samuel had never found?

Samuel opened the window a crack expecting the smell of manure, but the cold had squeezed the air clean.

A sign: Utica, 30 miles.

In the distance, to his left, gray smoke curled from the horizon's edge. He followed it with his eye as the highway curved to reveal the small figure of a man stoking -- what? -- debris or hay or something of no more use to him. It occurs to him now that Nurse Grayson, who’d summoned him to Boston, who knew Petey in the nursing home during his final illness, had not mentioned cremation. Why? Samuel thought of smoke rising from. . . where would the smoke rise from? No image came to mind. But ashes. There would be ashes, spoonfuls of ashes. Or would Petey be measured by the cup? or the quart? How much of Peter would there be? Less, if he had shrunk with age, and Samuel felt an impulse to giggle -- labeled inappropriate as quickly as it transformed itself into a lump in his chest, a small convulsion. For a moment the fear of stroke returned . . . or could it be a seizure? A newly considered pathway for his body's demise. But it came in even pulses and the wetness of tears brought to mind the name of the thing, itself: a sob. I am sobbing, he thought, as his vision blurred, his mouth tasting of salt. He grippedthe steering wheel, afraid to lift a hand to wipe his eyes; and through the tears he read the sign promising Albany some number of miles ahead, thinking the number should be noted when it was much too late, regretting he had not bought cigarettes with the coffee and candy bar,recalling his first cigarette, a Lucky, and the coughing, laughing with Petey and Cousin Mickie on the smokes swiped from Ma's purse.

Mozart had long faded to static, and the blood-sugared sadness Samuel felt distracts. His fears: the punishing scrape of kidney stones carving their way through narrow inner passages; a stroke or seizure (they seem as one to him just now). The loss of memory, of lucidity, is easier to bear than images of Peter reduced to ash. He veered abruptly from the far lane -- the wrong lane,he'd name it moments later -- to the right, towards a beckoning Howard Johnson's, failing to twist his head to see into the blind spot he'd dutifully checked for fifty-some years. A horn bleeps. Catastrophe averted by what? an inch? a foot? You'll kill yourself, old man, before your body does you in, he thought, and judged the irony fit but uninspired.

He eyed the dozen cars and trucks gathered in front of the brightly lit entrance as if it were a hearth; the restaurant was something generic, a fraud, a goddamned fraud, Howard Johnson’s being a phantom memory. Samuel picked a spot a good distance away. He shaded his eyes from the sun, which had wrested free from a blanket of clouds to break the gloom, reminding one and all it was still day. He did not want to be seen, even by strangers. He'd thought old age to be a time of clear-seeing through the muddle of emotion. A wiser, larger Samuel, he’d be. Not this. When had he become so brittle, fearful? He searched for a time and date, but he might as well reach for the stars in an expanding universe. Or was the universe contracting, collapsing like Samuel, himself? In the posing of the question he felt on solider ground. The image seized him, and he saw the stars as not simply receding, but fleeing. Yes, fleeing is the truer word: fleeing from the moment of conception, the Big Bang, the thought of which brings a chuckle, audible to an audience of one, Samuel, alone in this car, which has become a kind of home to him, and who now found strength to wipe away his tears.

In the silence, he finds comfort. I am pulling myself together, he thought, enjoying the phrase, imagining his emotions -- the tears, the heart-pounding fright over the near accident -- as a force, scattering his bones and limbs and sundry organs. Now fully collected, he steered back onto the highway. Found his place in the even flow of cars. For a few miles he endured the radio’s hiss and crackle, afraid to take dim eyes off the road to finger fumble buttons and knobs. Then, from the static, a melody, some words, but a mile or so goes by before the ache in Billie Holiday’s voice emerged; the hiss and crackle were in her voice now and not behind it, her defiant sorrow came in hesitations, then full-throated, seemingly birthed from the flatness of theland, and within Samuel a feeling grew and grew until he felt near to bursting with it, and there he was, hurling a baseball an inch under the chin of another boy, Charlestown Sammy’s knockdown pitch, and he felt again the bravado, the standing tall, erect, on the pitcher’s mound, the corner of his eye catching Petey and Da watching on the sidelines, aglow.

End of guest post

This story is protected under international copyright law and cannot be published in any format without the permission of Michael Alenyikov, who retains all ownership rights.

I thank Michael for allowing me to share this wonderful story with my readers.

Mel u

No comments:

Post a Comment